My friends know that I work two jobs—overpaid county physician by day, unpaid Seal Beach City Council watchdog by night. Usually, one has little to do with the other.

However, when reviewing the police contracts that the council approved at their last meeting, I have to wonder if one of the tenets that I learned in medical school might not apply to our local government—“the cure should not be worse than the disease.”

In this case, the “disease” that threatens our city’s financial health has been accurately diagnosed by our city manager—rising police pension costs.

His recommended treatment was to establish a two-tier system with lower pension benefits (“2 percent at 50”) for new hires.

However, to get the police unions to agree to this concession, the city offered a generous package of increased pay, vacation, and health care benefits to current officers.

So generous, that I feared that the cure was worse than the disease.

Whether this was the case or not was unclear from the financial analysis prepared by the city.

Consequently, I requested the raw salary data and re-crunched the numbers myself.

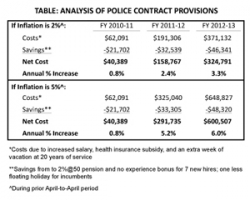

What I found was of concern. In every year of the contract, the costs of the enhanced package for incumbents far exceeded any savings that we can reasonably expect from hiring new employees under the cheaper pension plan (see table right).

I even tried figuring in the savings from two other concessions made by the unions—dropping one of their three floating holidays, and eliminating pay bonuses for new hires with prior police experience.

Even still, I found that the net cost of police salaries and medical insurance will rise faster than the rate of inflation.

City staff stressed repeatedly to the council that as more officers retire and are replaced by new hires, the savings from the two-tier pension plan will increase in the future.

This is true, but we only have 30 officers, and my calculations assumed that seven would be replaced during the three-year term of the contracts.

Fourteen of our incumbents were hired within the last six years, so they are not likely to leave anytime soon.

The problem is that the lower cost pension provision (“2 percent at 50”) only saves us the equivalent of 5.1 percent of salary for a new hire.

So even if all of our officers retired next year, the savings would only be about $150,000 per year (5.1 percent of a police payroll of about $3 million).

As the table shows, this would still not be enough to pay for the enhanced benefits that we promised in exchange for the two-tier system.

The new contracts may also have an unintended side-effect.

Over the term of the contracts, the city’s “Flex Dollar Allowance” will rise incrementally from $1,100 to $1,600 per month for officers with families. “Flex Dollars” are used by employees to pay for their health insurance, with any left over kept by employees as deferred compensation.

By January 2012, our officers will likely be getting more Flex Dollars than all other city employees, including the city manager.

If these other employees demand parity when their contracts expire in June of 2012, the cost to the city will be at least $300,000 per year.

So it looks like we have ended up with a cure that is worse than the disease.

Now the question is: how to pay for it?

According to the city manager, we can’t count on increased revenues anytime soon.

At least that’s what he told the council when they voted to expand the hours of operation for “Dial-a-Ride” program for seniors.

He made it clear that the additional $83,000 cost would have to come out of reserves or from cuts in existing services.

I just wish he had given the same warning to the council before they had voted 30 minutes earlier on the police contracts.

, I have to wonder if one of the tenets that I learned in medical school might not apply to our local government—“the cure should not be worse than the disease.”

In this case, the “disease” that threatens our city’s financial health has been accurately diagnosed by our city manager—rising police pension costs.

His recommended treatment was to establish a two-tier system with lower pension benefits (“2 percent at 50”) for new hires.

However, to get the police unions to agree to this concession, the city offered a generous package of increased pay, vacation, and health care benefits to current officers.

So generous, that I feared that the cure was worse than the disease.

Whether this was the case or not was unclear from the financial analysis prepared by the city.

Consequently, I requested the raw salary data and re-crunched the numbers myself.

What I found was of concern. In every year of the contract, the costs of the enhanced package for incumbents far exceeded any savings that we can reasonably expect from hiring new employees under the cheaper pension plan (see table right).

I even tried figuring in the savings from two other concessions made by the unions—dropping one of their three floating holidays, and eliminating pay bonuses for new hires with prior police experience.

Even still, I found that the net cost of police salaries and medical insurance will rise faster than the rate of inflation.

City staff stressed repeatedly to the council that as more officers retire and are replaced by new hires, the savings from the two-tier pension plan will increase in the future.

This is true, but we only have 30 officers, and my calculations assumed that seven would be replaced during the three-year term of the contracts.

Fourteen of our incumbents were hired within the last six years, so they are not likely to leave anytime soon.

The problem is that the lower cost pension provision (“2 percent at 50”) only saves us the equivalent of 5.1 percent of salary for a new hire.

So even if all of our officers retired next year, the savings would only be about $150,000 per year (5.1 percent of a police payroll of about $3 million).

As the table shows, this would still not be enough to pay for the enhanced benefits that we promised in exchange for the two-tier system.

The new contracts may also have an unintended side-effect.

Over the term of the contracts, the city’s “Flex Dollar Allowance” will rise incrementally from $1,100 to $1,600 per month for officers with families. “Flex Dollars” are used by employees to pay for their health insurance, with any left over kept by employees as deferred compensation.

By January 2012, our officers will likely be getting more Flex Dollars than all other city employees, including the city manager.

If these other employees demand parity when their contracts expire in June of 2012, the cost to the city will be at least $300,000 per year.

So it looks like we have ended up with a cure that is worse than the disease.

Now the question is: how to pay for it?

According to the city manager, we can’t count on increased revenues anytime soon.

At least that’s what he told the council when they voted to expand the hours of operation for “Dial-a-Ride” program for seniors.

He made it clear that the additional $83,000 cost would have to come out of reserves or from cuts in existing services.

I just wish he had given the same warning to the council before they had voted 30 minutes earlier on the police contracts.